China Completes World's Largest Radio Dish to Let

Scientists Hunt for Black Holes and E.T.

If great power comes at a great cost, the ability to peer deep

into the depths of the universe is no exception. For the world's largest radio

telescope of its kind, completed in China on Sunday, the price tag was

astronomical: the equivalent of about $180 million (roughly Rs. 1,214 crores).

The radio telescope also took a toll on local communities. Nine

thousand people - each compensated roughly $1,800 (roughly Rs. 1.2 crores) -

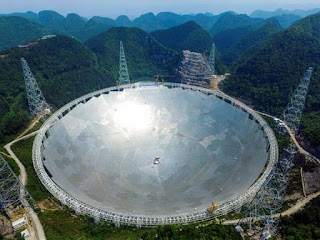

had to be uprooted to make room for the construction. The telescope is almost a

mile in circumference and covers an area equivalent to 30 soccer pitches,

embedded in a depression that acts as a natural noise shield.

But, to hear Chinese experts tell it, the radio telescope will

be worth every yuan.

"As the world's largest single aperture telescope located

at an extremely radio-quiet site, its scientific impact on astronomy will be

extraordinary, and it will certainly revolutionize other areas of the natural

sciences," the scientist spearheading the project, Nan Rendong, told the

Chinese state news agency Xinhua.

Known as the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Radio

Telescope, or FAST, the telescope claims the title of world's largest from the

Arecibo Observatory, a 300-meter device in Puerto Rico. FAST is so large that,

were the dish filled to the brim with merlot, it would hold five bottles of

wine per person on the planet, a scientist boasted to the Guardian in February.

Construction on the Chinese telescope began in 2011, though the delicate

arrangement of 4,450 reflector panels meant slow progress - just 20

installations per day. Workers placed the last of the triangle-shaped panels on

Sunday.

Radio telescopes may look quite a bit different than backyard

telescopes pointed at the moon, but their operating principle is more or less

the same. Instead of magnifying visible light, FAST channels and amplifies

radiation in the form of radio waves.

FAST is, essentially, a giant radio dish. There is a direct

relationship between size and sensitivity: The more space a dish covers, the

weaker the signals it can detect. Signals are funneled into receivers and then

boosted several orders of magnitude for analysis. Because the incoming signals

are so weak, cellphone chatter can overwhelm the cosmic waves. (Hence the

relocation of residents living near the dish in Guizhou province.)

"The bigger the telescope, the more radio waves it collects

and the fainter objects it will be able to see," University of Manchester

astrophysicist Tim O'Brien told the New Scientist.

With such a fine-tuned ear, FAST will listen for the radio

emissions from gravitational waves, black holes and the blinking neutron stars

known as pulsars. Even distant molecules, like amino acids, may be found with

radio telescopes; the devices are able to identify specific molecules as though

they had "fingerprints," according to Caltech astronomers, based on

the way they tumble through space.

The telescope should be fully operational for scientists by

September, and it will be capable of sensing radio waves from pulsars up to

1,000 light-years away.

And FAST will look for aliens. Earthlings, of course, have been

leaking radio transmissions from our planet for about a hundred years, which

means our detectable bubble is about 200 light-years across. Should there be

extraterrestrial radio waves being transmitted within 1,000 light years, the

South China Morning Post argued that the telescope might very well be the

device that finds them.

"The telescope is of great significance for humans to

explore the universe and extraterrestrial civilizations," said sci-fi

author Liu Cixin (once described as China's answer to Arthur C. Clarke), whom

Xinhua reported was on hand to witness FAST's completion.

FAST's completion comes at a time when China is expanding its

cosmic ambitions. In 2015, China announced its intention to land a probe on the

far side of the moon, a feat that has yet to be performed by any nation's space

program.

The telescope should outclass anything else constructed for the

next two decades, Chinese Academy of Sciences astronomer Zheng Xiaonian argued.

For the initial few years, time on the machine will be allotted only to Chinese

scientists, before opening up to international researchers later in the

telescope's lifespan.

No comments:

Post a Comment